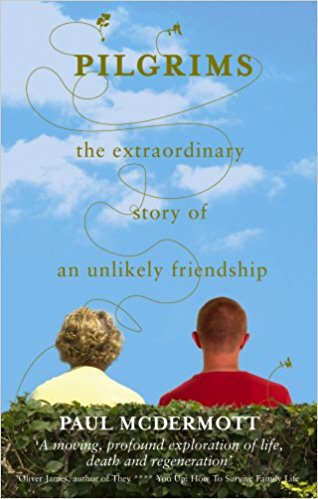

"A tender and intensly moving account of an extraordinary journey; a beautiful, human and uplifting story of transformation in the final chapter of life; ends shade into beginnings, and acceptance into discovery, as two ordinary people walk together through fear, emotion and personal history into an unexpected and healing vision of the truth. This book charts what is possible, with love and wisdom, when death brings us face to face with the ultimate meaning of our lives."

- Sogyal Rinpoche

author of The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying

"A moving, profound exploration of life, death and regeneration"

- Oliver James

author of They F*** You Up: How to Survive Family Life

Reader Reviews on Amazon:

- I read this book from beginning to end within 48 hours of receiving it. It tells the story of how Paul's commitment to visiting a dying old lady provokes a journey of self-discovery in him, and how their experiences, although very different, meet as he continues to befriend her. Paul's style in writing is excellent, combining as it does the harsh reality to life with stunningly poetic expression. In essence it is a very simple tale, but something magical lies within it. I experience from it honesty, courage, and acceptance all rolled into one. Paul's ability to affect another rubs off on me the reader in the same way it inevitably did with Val.

- I was deeply affected by this profoundly moving account of the relationship between a dying woman and a young man in search of deeper meaning in life. Essential reading to gain a refreshed perspective on life - and death.

- A book about life...the good moments, the ordinary moments and the ending moments. A book that is at times witty and sad but always honest...a thoroughly good read.

- I found this book extremely moving and the depth of the characters was extraordinary - you felt you were in the same room with them as there friendship grew and blossomed. A book to cherish and I wish he'd write another.

- A very moving story. A friendship based on respect and love and how two people brought together by circumstances develop an unbreakable bond.

For an article on me and Pilgrims that appeared in The Observer newspaper click here

a couple of early chapterS ...

TOM

14 October 1993

I waited in anxious silence outside the house of someone whose death had come alive in them. I sat in my little car, pretending I was fine and relaxed and that nothing phased me. I liked to give the impression, even to myself, that I was not still a mess inside. I waited on the side of a road that curved away before and behind me just as it was designed to in the town planning office. I was confronted by a profound sense of barrenness, inside and out. This street and I, we were not a part of life at all, we were on a stage. No other cars cluttered the side of the road; they all had their own pre-planned little driveways and garages. No children played on the streets, no dogs dared bark, no pedestrians ruined the effect by venturing out on the pavements. Not even the trees seemed to stir. Nothing moved, nothing made a sound. The houses seemed to be holding back, listening. It would not have been out of place if a tumbleweed had rolled down the road accompanied by the lament of a single quavering note from a mouth organ. Except this was an autumnal England.

The property belonged to an elderly woman who lived anonymously, and acrimoniously, in this small military town. The house was a modest 1950s semi-detached, mirrored and repeated out of sight in both directions: plain, uninteresting, indicating by its very design that nothing of any significance was meant to happen within its four walls. Yet I awaited my appointment with her dreading and hoping all. My gut felt cold and empty. What on earth was I doing there?

As I sat sweaty-palmed in my car I began to regret being involved with the hospice charity at all, feeling a vague nostalgia for the 9-to-5 security of the 1980s: wake up = radio STRAIGHT on in case I was immediately confronted by one of my own thoughts; wash = radio on louder; eat = news on the radio and a newspaper and 'Thought for the Day' in case another one of mine slipped through the net; the underground = walkman playing something I thought would impress the sort of woman I would want to impress if she asked to listen (which she never did); the International Stock Exchange = computer screens and meetings and documents and meetings; a workout at the gym = eye-level MTV with dancing girls who were not interested in what was on my walkman; home = television; bed = racked by paranoia and self-loathing and every little interaction of the day scraping painfully across the rasp of my ego as I searched forensically for criticism or blunder.

A district nurse pulled up in front of me in her own little car. You could feel the twitching curtains along the road. She interrupted my paranoid reverie by introducing herself, but I was so distracted that I missed her name entirely. I moved with her towards the ominous little house now not only anxious but also slightly disoriented. Death was in there, and I wanted to face it, again, face something definite. I had already realised that if I wanted to truly understand something, I had to stand right in front of it, all by myself.

We crossed the road in an awkward silence. I didn't feel so good, and suddenly I was desperate for a pee. 'A deep breath and a leap,' whispered Goethe as I arrived at the front door, a door that would become as familiar to me as my own. I rang the bell and a submerged figure appeared beyond the watery glass. Like water tends to do, the distortions of the glass made whoever was behind it look very short and stocky. The door opened and there the old woman stood, proudly erect at five-foot, barrel-round. She grinned broadly at the nurse, glanced at me in a pleasant but cursory fashion and indicated, by walking off, that we should follow her inside. I sat when invited on a huge sofa and stared nervously around a room so valiantly decorated it increased my growing unease. The ceiling hung low, covered with dirty polyurethane rectangles full of tiny holes like a battalion of factory-made rain clouds. Cornicing was glued around the edges to keep the clouds in the room, drifting only eight feet above a typhonic swirl of pattern and colours: Gaudian wallpaper hung heroically over Daliesque carpet. There were dark laminate cabinets, the colossal fake velvet sofa with matching chairs, and sitting mightily against the wall the brooding ever-watchful television set. I thought rather irreverently that I too would be seriously ill if I had to live in that dense kaleidoscopic frenzy.

The room conveyed the sense of a life defined, referenced and shelved; an impression that little had actually happened other than the gradual accumulation of this flotsam and jetsam. Perhaps I was just one more piece. Yet each small object had some self-importance about it, much like the woman I had come to visit. And there sat I, about to be born into her world, before she could no longer tell anyone about it, before she went completely cold and was burned to dust in a furnace. By now feeling seasick, I was horrified when the nurse suddenly stood to leave. I stood with her and smiled weakly, torn out of my interior's delirium by the look of pity and hope that flickered across her eyes. As I sat down again to stare at the veneer coffee table that pressed urgently against my knees, I felt alone and exposed in a way that felt familiar. I had been cast out upon some vast ocean with neither map nor compass, needing to learn how to navigate by the stars alone. It felt dreadful. It was perfect.

What if I stood up and said 'I've just got to see a man about a dog.' And before she knew it I'd be out the front door and into my car and off down the road? I'd drive all the way to southern France, and live off my credit cards. In summer I would press grapes with my bare feet with French girls with their full black skirts pulled up over long brown legs. I would slowly learn the language. And fall in love with a dark-eyed, dark-haired young woman, slight over-bite, perfect little breasts, and we would marry and have children. Then there would be this huge flood and I'd save the young and the elderly and everyone in the village would love me. 'Tea?!'

I followed her into the kitchen like an unmoored boat drifting with whatever tide the moon exerted. From the kitchen I got another angle on the garden that was visible through aluminium sliding doors at the end of the lounge. The garden was rectangles, flanked on the right by a dead straight concrete path. There was a contained rectangle of grass, a rectangle of vegetable garden, and two rectangles of stone paving, one by the sliding doors and one at the far end, which ended in a vertical green rectangle of hedge.

She saw me staring out at the parade of garden and, as if reading my mind, said, 'Tom was in the military.'

'Ah,' I said, in perfect French.

We returned to the lounge and sat, tea in hand, at oppo site ends of the consuming sofa. She told me about receiving her death sentence and finished her monologue with 'But at least I had Tom.' She went on to tell me that one month after she had been diagnosed, her husband of forty-eight years had also received a diagnosis of cancer. At least his prognosis had been better than hers, which meant that he would be there to look after her until she died. But he had not managed this. Tom had died within a month of being diagnosed. He had died emptying his bowels on their bed upstairs.

Val had sat at his side bewildered and frightened, as I now sat at hers. Suddenly she was not only dying but acutely aware that she was dying. She thought in those Arctic moments that it was she who was supposed to die first, and that he was supposed to be there looking after her. She had looked at her husband, dead on their bed, and thought to herself, now strangely alone in the room, 'This will happen to me.'

That was where I came in.

THE WALL

22 October 1993

Val was seventy-four when we met, and although it is a bit rude to say so, she looked all of it. If you have seen the Star Wars films, you may remember Yoda, who was clearly based on this woman: a squat, amused, wrinkled being with an air of mischievous awareness and a penetrating stare. That, with a smear of red lipstick, but without the cloak and pointed ears, was Val. The week after my first visit I rang her doorbell and noticed it took her a couple of minutes to swim from the sofa to the glass front door. On surfacing she beamed up at me from the doorway. I looked down smiling, but in my mind went, 'Oh my God, why hadn't I noticed that before?' From her gaping mouth protruded three (only) teeth so separated from each other that each appeared to be leading a life entirely independent of the others.

I found myself slightly more immune to the decor, and once offered a seat on the sofa I sank quietly down, and down, as if in quicksand, my arm protruding from the crevice between cushions, then only a hand, then gone, forgotten.

It was not the sort of visit one begins with 'How are you?' because the only honest answer is 'I'm dying. How are you?' So I gave an impression of sitting quietly and calmly that seemed convincing enough for Val to begin talking, which she would always do in her own time and her own way. She idly chatted about the 'news' and the weather and what nurses had visited her until she came to inviting me to share some tea with her. She did this with a delighted affection for the word itself, as if she had by chance stumbled upon this long sought-after treasure: 'Tea?!' Big grin. Three teeth.

A photograph of Tom in uniform looked down on me, in more ways than one, from the bookshelf at what was to always be Val's end of the sofa. Tom looked as though he expected to take the lead, to go on ahead. He had.

Not being a fan of English tea - I liked to pretend I had left behind a need for the homely reassurance offered by milky tea for a Zen-like independence - I tried to leave my lukewarm cup without saying anything. I hoped this would go unnoticed. It did not. I didn't want the tea, but I also didn't want to hurt her feelings. On this, my first solo visit, I was to do almost everything wrong. It was to take some recovering from.

'What's wrong with your tea?' Val demanded, looking exasperatedly from the cup to me and back again.

'Just letting it cool down a bit,' I said. Sometimes a lie would just pop right out of me like that, before I knew it was coming, like it was dad on my case and I was in deep trouble. My penance from that time onwards was that she would add so much milk as to make it no longer tea at all, but something more like lukewarm milk that had had a brown crayon dipped into it. 'You like it not so hot, don't you?' she would say. I worked out my karma and drank the 'tea'.

'Another cup?'

Like an idiot I said, 'Yes, if you're making one.' 'Well, it's not about to make itself, is it?'

This time she delivered the tea with the teabag still in the cup and a teaspoon for me to retrieve it but no saucer. I wondered where to put the bag once it was out.

Val appeared to enjoy my shy discomfort, enjoyed being entertained for a change. I was beginning to notice how acutely she was observing me, as if I were a patient possessed by some unknown affliction that she would eventually diagnose and then give me a prescription for.

'You can just leave it on the spoon (pause), but it will go in the rubbish bin under the kitchen sink (pause). That's the compost (pause). I was told you do gardening.' Val was pacing her speech so that an imbecile could understand her. Gardening? I'd had little experience of gardening other than lawn mowing. When I was thirteen, I used to ride my bicycle over to my father's friend's house to water his plants while he was away in Australia. It was a very hot summer, and I used to enjoy standing there with the hose. I would watch the water rainbow over the thick-leaved plants, the reassuringly dense smells of damp earth and wet warm concrete. The kidney stones of my home life seemed to wash away from me, like the gravel that washed out of the plant beds to sluice down the driveway. I would stand there quiet on that hot concrete driveway, thinking about how I would spend the money I was so easily earning.

It was just wonderful. But I didn't get the job again the next time dad's friend went away, some problem about gravel loss.

'Oh,' was all I managed to say to Val's confusing me with a gardener, but it was I who was confused about why I was there.

She went on, without missing a beat, to give me the facts of her life. She was born Evelyn Turner, with Europe rever berating from the Great War. As a young child she was told that her mother had been a prostitute who had given her up to an orphanage. She remained there until the age of four teen, the end of the Great Depression. She was adopted by a couple who could not conceive children of their own and, as so often happens upon adopting, the mother immediately fell pregnant with the first of her own children. Val was left in the somewhat unexpected position of having siblings to compete with for love and attention.

The remainder of her adolescence, and in fact the rest of her life, was passed in Aldershot. The town was gearing up for the Second World War when Val applied to the Post Office for a job, where she remained employed until she retired. In 1936 she had met Tom Hall and through him found at last a family, Tom's family, who welcomed her unreservedly and as one of their own. Three years after she met Tom, the Third Reich drew England into war. With Val turning twenty years of age, Tom enlisted in the air force and went off to fight.

Although they were engaged that same year, it was another three years before Tom and Val were married, on April Fool's Day. Ten years later their daughter Christine was born, an experience Val found so physically horrendous that she decided then and there that Christine was to be her only child. This event seemed to confirm to Val what she had suspected for years: that her marriage was the enemy of all that was vital, original and promising.

Val said all of this in a measured, matter-of-fact way, until she suddenly slumped forward and dropped her head toward her lap. She had begun on the story of her life from the time of her daughter's birth, a territory unexplored since the events themselves. She found then and there in her little low room that the power of these memories was such that it could easily buckle her. They pulled her down bodily as well as emotionally, into the quiet resignation that had become the background to her being-in-the-world. Val felt her life had been extinguished at Christine's birth, not as a result of Christine herself but of what being a mother came to mean to Val: the forfeiture of her own biography. To her, all that was possible and hopeful in her life had been scup pered. She saw ahead only a predictable posthumous pedes trianism. Her life was to become uniform, not unlike her garden - trimmed, fenced, concreted over where deemed prudent.

'And I didn't like it,' she said. 'I never liked it. I just did it because I felt I had to.' She sobbed and leaned forward, her head in her hands, her elbows resting on her knees. This was not what I had been expecting. I tried to beam rays of Empathy and Congruence and Unconditional Positive Regard at her, because that was what I had been trained to do. Inside I was beginning to flounder.

'I think sometimes I should just have let him go with that woman,' she said into her palms. 'I don't think he ever forgave me for that.'

What woman? Had she talked about a woman? How could I have missed that?

We were sitting at separate ends of her sofa. I wanted to help. It was terrible what I did, crushing: I slid along the sofa, without being invited, and put my arm around Val's shoulders. It was in the Manual, Chapter 2, Hugs and Tissues. She sat bolt upright, immobilised and tense. The sobbing stopped, immediately, possibly permanently. I was left in the embarrassing position of sitting there with my arm draped around her like she was my girlfriend, the used teabag discarded on the table. I suddenly had a craving to run. As I tried to surreptitiously withdraw the offending arm, she glanced up at me. I saw in her face years of pent up anguish, dammed up once more against an unreceptive world. I was that world.

'Sorry about that,' she said.

Those should have been my words: Sorry Val, I apologise - it was me. I've been trained to do that sort of terrible stuff to people. I am an abomination.'

'I don't know what came over me,' she said, painfully, for both of us. And I let her. 'It must be the steroids.' She stared into a familiar abyss of lost opportunities.

'I'll make us a cup of tea,' she said as she pulled herself up and out of the depths of the sofa and memory. She slowly made her way back to her kitchen, defeated. Frozen to my seat, appalled at what I had done, I couldn't budge. Inside I shouted at myself, 'Bugger! Bugger! You stupid bugger!'

I might as well have leaned over and punched her when she had begun to cry. Thwack! 'Pull yourself together, woman! Worse things happen at sea!'

On Val's return from the kitchen, the glacial void I had engineered echoed with polite, empty conversation. She said, 'I went ... '

'Oh, did you?'

'Yes, it was lovely and ...' 'Sounds nice.'

'Did you see that programme on ..?' 'No, I missed it.'

'It was all about ...

' 'Really.'

'Yes, and ...' 'Mmmm.'

'Still, you must be very busy today.'

' '

'You've got all your hospice work and things.'

' '

'Don't let me keep you.'

When I left Val didn't look at me. I was hoping for some look or word of reassurance. Everything was the wrong way around. Quite rightly, no quarter was given. I left her that day feeling worse than useless: I was an impediment.

When I returned the following week, we resumed what became our usual places on the sofa. But now there was a pile of magazines over a foot tall between us. The Wall. Neither Val nor I mentioned its presence. It was the Iron Curtain; it was Cold War Berlin in that little room. It was humiliating and intimidating, but this time for the appropriate person. Rooted into that sofa - Val, the magazines, and I - like her three disparate teeth, ostensibly united in purpose yet already separated by a seemingly unbridgeable breech.